By: Kaylee Smit

South Africa continues to strengthen its pivotal role in deep-sea research, making contributions that are significant for Africa, relevant within the Western Indian Ocean, and valuable to the wider Global South. From 27 July to 5 August, the NRF-SAIAB, under the umbrella of the South African Polar Research Infrastructure (SAPRI), which is funded by the Department of Science, Technology and Innovation (DSTI), hosted a field-based underwater observation training workshop in East London.

The Workshop was convened to address the growing need for specialised skills, shared standards, and collaborative networks in underwater visual observation research, particularly in the deep-sea. Its primary aim was to provide hands-on training in the use and application of remote imagery technologies, with a dedicated field-based training component to collect real survey data from previously unexplored areas along South Africa’s east coast.

The initiative sought to build technical capacity, foster international collaboration, and support the development and refinement of standardised approaches to marine biodiversity observation and ecosystem assessment. The workshop brought together an international team of researchers, students and technicians from South Africa, Seychelles, Cape Verde, and Trinidad & Tobago to gain practical experience with Baited Remote Underwater Stereo-Video Systems (stereo-BRUVs) and deep-water lander platforms. These technologies are transforming marine biodiversity research by enabling non-invasive observation of fish and other marine life from shallow reefs to the deep sea.

Left photo: Dr Anthony Bernard, an instrument scientist from NRF-SAIAB, conducting a presentation on an introduction to baited remote underwater stereo-video systems (stereo-BRUVs) research and the new deep-water lander platforms, both shown in the foreground right and left, respectively. Workshop participants are actively engaged.

Right photo: Danielle Julius, a marine science technician from NRF-SAIAB, conducts a training session on camera calibrations and video annotation for workshop participants, which sparked lots of technical discussions and shared learning.

Pioneering Technology in Action

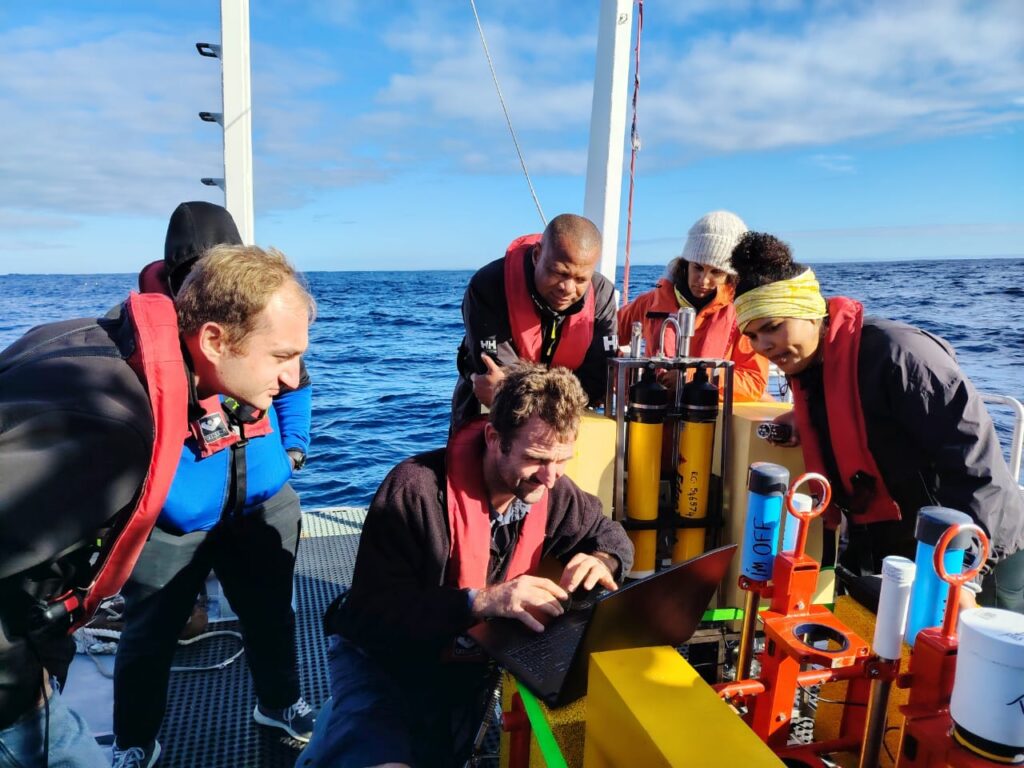

A key highlight was the first field test of a brand-new, 3500 m-rated “abyssal lander”, developed in collaboration with Sea Technology Services. This fully untethered platform extends South Africa’s observational reach far beyond the continental shelf into unexplored bathyal and abyssal habitats. Notably, the engineers who designed and built the lander participated in the training, leading demonstrations, troubleshooting sessions, and refining deployment protocols. This direct engagement provided rigorous operational testing under real conditions while also transferring technical knowledge from the designers to the scientific end-users.

Left photo: In all its glory – “Karel Groot Oog”, aka Karel, as named by vessel skipper, Koos Smith. The new deepsea abyssal-lander that is currently depth-rated to 3,500m. This workshop marked a milestone as the very first test deployments of the lander, reaching a maximum depth of 2,351 m. To commemorate the achievement, participants and crew signed the foam as a lasting memento of the day.

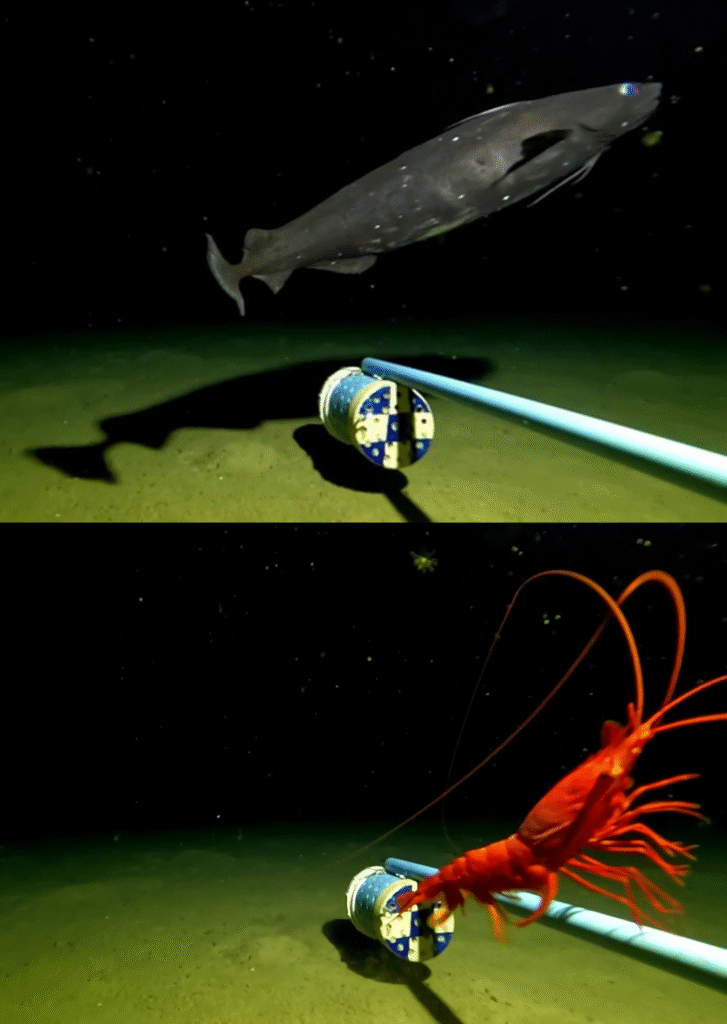

Right photo: Deep-sea violet cod (Antimora sp.) and an unidentified shrimp captured by the abyssal lander at 2,351 m depth at the bottom of a South African submarine canyon. Although the screenshots are slightly blurred, these rare visuals offer valuable insights into life at extreme depths.

During the workshop, the team achieved a South African deep-sea record for scientific stereo-video observation, with the abyssal lander successfully reaching 2,351 metres and collecting five hours of continuous video footage. Among the highlights was a striking encounter with a deep-sea violet cod (genus Antimora) gliding gracefully across the seafloor, accompanied by the sudden appearance of an as-yet-unidentified shrimp – rare glimpses into life at these depths.

“I was excited to explore the deeper, unseen parts of our submarine canyon and slope ecosystems and to uncover key insights to better understand this unique region,” said Luther Adams, a PhD student studying shallower shelf ecosystems in the area.

These deep-sea missions were complemented by multiple deployments of the original stereo-BRUVs landers (now affectionately called “The OGs”), at depths from 300 meters to 1,200 meters.

Left photo: Anthony Bernard and Danielle Julius, from NRF-SAIAB, waiting in anticipation to deploy the deep-water lander-BRUVs (one of the OGs).

Right photo: Team photo from our first successful sea day, where all three lander-BRUVs were deployed and safely retrieved – a rewarding day of hands-on training and plenty of smiles.

Building Skills and Networks

The training also included multiple land-based training sessions on stereo-BRUVs research, equipment preparation, data management, calibration, and video annotation using SeaGIS EventMeasure software. Throughout the workshop, participants discussed barriers to deep-sea research in developing nations and explored how collaborations and shared research platforms could provide solutions.

Hands-on sessions sparked many technical discussions about the potential applications of different equipment in various countries and contexts. Reflecting on the experience, participant Ryan Manette, from Trinidad and Tobago, said:

“Practical field training on the boat was most useful for me, as I got to see the actual workflow and logistics for deployment and retrieval of the equipment. What I liked most was having an active role in the deployment and retrieval of the landers – the excitement of deploying them and the relief when they were back safely on board.”

A team photo of the second batch of workshop participants who successfully deployed and retrieved three lander-BRUVs. It was a fantastic day of learning and exploring.

Impacts and Legacy

The knowledge and skills shared during the workshop will directly strengthen deep-sea biodiversity research capacity in participating countries, contributing to global efforts to map, understand, and protect ocean ecosystems. This supports the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 14 (Life below water) and 17 (Partnerships to achieve the Goals).

This training also marked the beginning of the newest deep-water research project undertaken in the Seychelles by Sheena Talma, a former NRF-SAIAB student and National Geographic Explorer. In her upcoming expedition, Sheena will apply the methods and technologies demonstrated during the workshop, in collaboration with NRF-SAIAB, to collect critical marine wildlife data in key fishing areas within Seychelles’ waters. The goal is to inform sustainable fisheries management and deepen understanding of the region’s largely unexplored deep-sea ecosystems. Her project forms part of the National Geographic and Rolex Perpetual Planet Ocean Expeditions, a series of pioneering scientific research missions across the world’s oceans – from seashore to seafloor and from pole to pole.

New visual data from depths of 300 meters to 2,300 meters were collected, providing information on deep-sea species, their size and geographic distributions and habitat associations. These data will inform habitat mapping, ecosystem classification, marine spatial planning and identification of priority conservation areas. The successful testing of the abyssal lander also opens new frontiers for deep-sea exploration, paving the way for discoveries that could enhance conservation planning and the sustainable management of ocean resources.

Left photo: An aerial view of the NRF-SAIAB research vessel, Observer, as the team prepare to deploy the last lander-BRUVs to 300m.

Right photo: An important moment of checking the camera and light settings, in preparation to deploy the new 3500m-rated lander for its first ever deep-sea sample. Dr Anthony Bernard runs through the final checks with the workshop team, including Johan Loubser, the engineer from Sea Technology Services.

The impacts, however, extend beyond technology and science.

“This workshop was about more than just training – it was about building a connected, skilled network of scientists and technicians who can work together to unlock the mysteries of the deep sea,” said Dr Kaylee Smit, Senior Research Fellow at NRF-SAIAB and the lead organiser. “We really bonded over the 10 days we spent together, engaging in meaningful conversations and building relationships that will carry into future joint projects and collaborative training initiatives – starting with Seychelles in 2026.”

That sense of connection was echoed by NRF-SAIAB marine science technician Danielle Julius, who reflected:

“I really liked how supportive and helpful everyone was, as well as how patient the conveners were in explaining how operations are done. It showed me how important it is to communicate with everyone involved in the deployment of instruments.”

Some of the female workshop participants showing off their new field gear, feeling very proud. From the left, National Geographic Explorer Sheena Talma from Seychelles, middle, Dr. Kaylee Smit and right, Danielle Julius, both from NRF-SAIAB

Although the workshop has concluded, its impact is only beginning. This growing network is ready to dive deeper, work together, and continue unlocking the secrets of the deep sea. Its legacy will live on through future joint expeditions, cross-training exchanges, and expanded capacity for deep-sea observation research across the Global South.